You’ve probably heard that parabens trigger breast cancer because they mimic estrogen. It’s a commonly held belief but like many beliefs about skincare, it’s not true. So how did these ingredients, the most common (other than water) in cosmetics, become entrenched in the list of verboten skincare ingredients?

Although the parabens’ journey to infamy began in 2004, I remember it as if it was yesterday. A producer I’d worked with from The Today Show called to find out what my opinion was of a just-published report from a British toxicologist who found parabens in 18 of 20 breast tumors. The doctor, a woman, attributed the preservatives’ presence to their inclusion in deodorants and antiperspirants, something I knew as a cosmetic scientist was very rare since these products tend to preserve themselves. Evidently, the news was causing a level 5 hurricane of concern among consumers, who insisted they immediately be removed from cosmetics. (Ultimately, many companies, especially in the professional esthetics arena, did remove parabens after months-to-years of researching alternative preservatives that had a history of safety for humans, animals and the environment; were effective on the wide variety of yeast, mold, fungi, viruses and bacteria that can grow in cosmetics; were compatible with the other ingredients in cosmetics; were readily available from ingredient suppliers; could be effective at low percentages; and which wouldn’t double the cost of the product - as it turns out many did.)

Shortly after the call, I invited my much-put-upon but passionately supportive husband to accompany me to our local drug and grocery stores where we reviewed every single deodorant and antiperspirant package on the shelves; at least fifty or more. Just as I expected, parabens were in none of these products. At that point, sensing a smelly pile of brown stuff was being shoveled at the media, my BS antennae went up.

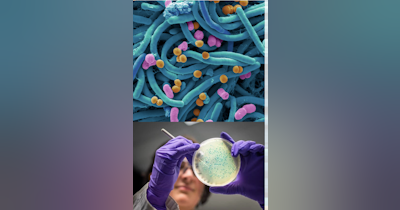

You see, parabens, which are widely used antimicrobial preservatives for cosmetics because they prevent the growth of mold, yeast and fungi, are among the most studied of all cosmetic ingredients and have a long history of safety. Although there is an Internet myth claiming that they have been banned in both Europe and Japan, it is not true. Parabens are allowed for use by every government agency that regulates cosmetics worldwide.

Used since the 1920s in thousands of cosmetics and pharmaceuticals, as well as in a few foods, parabens are a family of chemicals known as alkyl esters of p-hydroxybenzoic acid. They have various prefixes that refer to the length of the alkyl ester group that branches off of the acid. These include methyl, ethyl, propyl and butyl, which are allowed for use at low yet effective percentages in most countries due to their stellar safety profiles. Others - isopropylparaben, isobutylparaben, phenylparaben, benzylparaben, pentylparaben - are banned in the EU, not because they’re dangerous but because they are not used in cosmetics so there is little data on their use or safety.

Methylparaben is the shortest chain—or smallest molecule—of the group, butylparaben is the longest and the others are of various midlengths. Several parabens are found in nature, including methylparaben. This most popular variety is produced by certain mold species in order to protect themselves from hostile bacteria. However, to my knowledge, none that are used in cosmetics or other commercial products come from natural sources. Most of those utilized in cosmetics are derived from petroleum.

Throughout the past quarter century, parabens have been recognized as several of the more than 8,000 endocrine disrupters (EDs) in the environment (Hormonal Chaos: The Scientific and Social Origins of the Environmental Endocrine Hypothesis, Krimski, 2000). These chemicals, which behave like animal estrogens, can affect hormone balances adversely or disrupt the normal function of organs that are controlled by hormones. Among the more popular EDs are phytoestrogens, which are found in such common food, cosmetic and herbal supplement ingredients as soy, flax, hops, Angelica sinensis (dong quai), Salvia officianalis (sage), clary sage, red clover, pumpkin, poppy, St. John’s wort, rosehips, yarrow and some seaweeds. They now are believed by many researchers to contribute to the increasing incidences of breast cancer, low sperm count and other estrogen-influenced medical problems in humans, as well as to alter the sexual characteristics of fish, frogs and other species by contaminating fresh water supplies.

Although parabens are 1,000–2,500,000 times weaker than natural estrogenic compounds, with methylparaben being the weakest of the group, phytoestrogens are approximately 400 times weaker than human estrogen. But, due to the fact that parabens are used more commonly in cosmetics and foods, and because they are produced synthetically from petroleum, some researchers are more worried about their estrogenic effects but show little alarm regarding natural phytoestrogens.

I find this lack of curiosity, if not research into their safety, a little troublesome if not itself alarming. Just because an ingredient is natural doesn’t mean it’s safe, and many natural ingredients are found to be less safe than synthetics once they’re researched.

Because parabens are known to penetrate the skin, concern has been voiced by some researchers and consumer watchdog organizations that those that are included in cosmetics might act as EDs when applied to the skin. Cosmetic chemists who are familiar with the skin-penetration activity of parabens maintain that this is not possible because, once they enter the skin, they form metabolites that are a result of enzymatic processing by skin cells. While paraben metabolites were once thought of as incapable of mimicking estrogen, several studies in the last five years indicate they are estrogen mimics but weaker than the original parabens.

At the beginning of 2004, a study was published by an English toxicologist that seems to put this accepted scientific knowledge into doubt (Concentrations of parabens in human breast tumours, P. D. Darbre, et al, 08 January 2004). Phillipa Darbe, PhD, a senior cancer researcher at the University of Reading in the United Kingdom, reportedly stopped using antiperspirants in the mid-1990s, due to a gut feeling that they were connected to breast cancer. Seven years later, she looked for the presence of parabens—ingredients she believed were used in these products in deodorants and antiperspirants—in 20 breast tumors and found them in 18. Although stopping short of stating that the parabens came from underarm products, she did claim that the chemical form of those she discovered indicated that they had been applied to the skin, rather than consumed. She advised that further research be completed in order to determine their source.

Unfortunately, Darbe’s findings have been misreported widely by news agencies, consumer awareness organizations, cosmetic companies and others as proving that parabens cause breast cancer, with the likely contributors being antiperspirants and deodorants. Some reports even state that the Darbe study shows a clear connection between these products and breast cancer. It does not. Even Darbe admits this.

In January 2005, the European Union’s Scientific Committee on Consumer Products (SCCP) published an opinion paper that evaluated paraben safety in relation to breast cancer (Extended Opinion on the Safety Evaluation of Parabens, SCCP/0873/05. 2005). Shortcomings in the Darbe study are among its findings. These include the following:

- A lack of control tissue against which to measure paraben levels in other areas of the body or in breasts that did not contain tumors.

- No report of the subjects’ therapeutic history, which may have uncovered other sources of paraben exposure.

- No mention of the paraben-containing anti-cancer drugs that the tumor subjects were using.

- No report of the subjects’ exposure to consumer products containing parabens.

- No description of how the tissue was handled. Contamination could have occurred then.

The SCCP report also notes that methylparaben was the most frequently occurring paraben found in the breast tumors, yet it contains the lowest estrogenic activity. The strongest estrogen mimic—butylparaben—was the least represented, probably due to its larger molecular size. And, although Darbe suggests that the paraben source may be underarm cosmetics, the SCCP states that 98% of underarm products, including deodorants and antiperspirants, do not contain them. Therefore, it is highly doubtful that the substance could have come from these products.

The SCCP concluded that “There is no evidence of demonstrable risk for the development of breast cancer caused by paraben-containing underarm cosmetics,” especially in view of the weak estrogenic potential of these ingredients. “With regard to their general toxicological profile, acute, subacute and chronic toxicity studies in rats, dogs and mice have proven parabens to be practically nontoxic, not carcinogenic, not genotoxic or co-carcinogenic, and not teratogenic (i.e. fetal toxicants).”

Well, that pretty much sums up the estrogenic issues with parabens. As I told The Today Show producer eighteen years ago, parabens as we use them in cosmetics are safe. And to date, no one has proven otherwise. That statement still stands in 2022.